Through twelve evocative tales of longing and loss, Exiles Incorporated depicts a volatile world of hostile landscapes, where humans strive to belong amid the cruelty of conquest, the madness of desire and the transience of love. In the seventh story Janeiro, set in 16th century Brazil, a conflicted Jesuit and a bullied Tupi lady forge a union that transcends time and space.

Drifting towards each other from opposite directions, the two strangers arrived at the blackened plant in the wasteland together. The charred tree stump jutted six inches from the ashes, like a dark fist punching through the earth. It was the solitary landmark in the grey, waterless plain, save for the depression in the ground where the river once ran.

“The source of the signal.”

“Could do with watering.”

“Your kind have a sense of humour, then.”

The stump’s top, shorn flat during deforestation, was a smooth black surface without growth rings. The moon’s reflection lay suspended in its centre.

“You really think this is where it happened?”

“It was a different time back then.”

Together they imagined an emerald landscape of trees, villages and colonial ships prowling the coastline. Now there was no coast. Greed and fear had long since burned away nature’s nervous system, leaving only a petrified expanse smothering the earth.

“At least there’s nobody left to torch outsiders.”

“This resisted the fire.”

“Just about.”

“Why them? They were nothing special.”

“Special enough to induce an extreme reaction. The last of its kind.”

“Or the first.”

The strangers let their breaths intertwine over the burnt wood.

“It’s still alive.”

“How do you know?”

“We’ve started speaking the same language.”

***

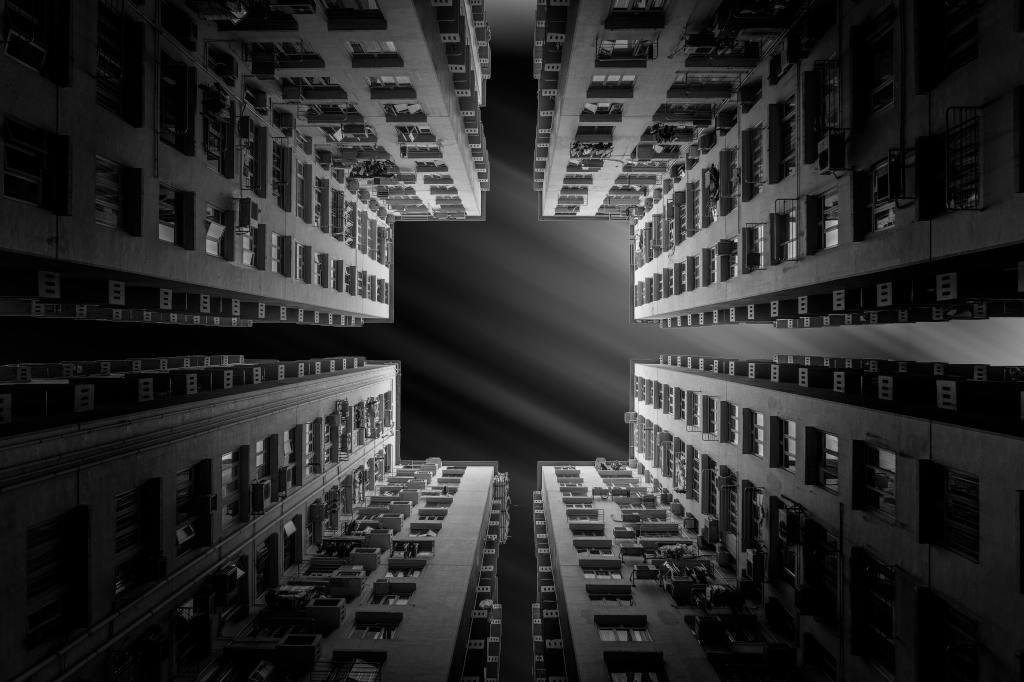

Everyone understood the command, no matter where they came from. The Governor-General demanded mercenaries pack the cannons with gunpowder. Grim circular faces of heavy iron cylinders pointed across the bay, so militia on the fortress turrets could unleash fire on rival colonialist ships. After all cannonballs were exhausted, the men would count the driftwood on shore. Routine would return. Unoccupied hours watching the rivers emerge like open veins from corpulent emerald country.

A fragile peace held on this strip of South American coast. Swords and smallpox had quelled the indigenous Tupis. Taking their place were merchants, artisans, farmers and slaves. Degregados too: miscreants fleeing their motherlands to suck the breast of the new world. Compliant Tupi lived in new mission villages on the plateau. Several toiled at sugar plantations up the coast. Others slaved on ships bound for Europe, loading the vessels with nature’s bounty from tortoise shells to topaz. Many had fled deeper into the brooding forest.

The settlement was named Rio de Janeiro. River of January. A natural wonder first seen by European eyes on the first day of the first month. A new channel through which earthly riches and God’s love could flow in abundance. Spearheading the advance were the Jesuits. They’d braved the Atlantic to teach Christianity, Portuguese and Latin to the Tupi, so the savages could savour the sweetness of God’s language on their tongues.

Some settlers were less convinced. Lonely exiles from the old world sensed holy words might run aground here. In the stillness after supper, drifters meandered towards each other around jittering fires. Speculation ensued as to what lay in the forest’s guts, from two-headed monsters to voluptuous witches drinking the blood of their young. Some conjectured the forest may even be one enormous creature. To wound one leaf would be to wound them all, provoking an earthly wrath that would freeze speech and curdle the soul.

Under a full moon, tensions thickened. Mirthful evening chatter tapered to silence and ended with twitching gazes into the dark. Panicking flickers of white light appeared in the trees then dissolved. Seething spasms of sound rumbled from the unsettled water. Branches creaked and stretched, like the forest’s nerve endings craved new sensations in the tender air.

The last to fall asleep dreamed the moon and the earth were in dialogue. The two celestial objects shared an alien language, the visions went, channelled through primeval waterways that pleaded for an intimacy neither describable in words nor conceivable in the mind.

Exiles Incorporated is available to buy on Apple Books, Amazon and Google Play as an e-book, plus on Amazon and Barnes & Noble as a paperback.