Whether it’s a question of greed, survival, insanity or sheer hunger for power, stories about cannibalism give you plenty to chew on.

“One calls barbarism whatever he is not accustomed to,” wrote Michel de Montaigne in his famous essay Of Cannibals. Eating another person may be taboo in our civilised world, but as the French philosopher suggested, it’s also a question of context, culture and circumstance.

Filmmakers hungry for shock and provocation have gorged on this moral relativism, and the spicy dramatic potential inherent in seeing people eat other people. Cannibalism offers a rich diet of homicide, depravity, survival ethics and otherworldliness, not to mention the fear that’s haunted everyone since first hearing Little Red Riding Hood as a child. Out there are wolfish predators in human clothing, the story goes, who’ll gobble you up if you’re ever lost in the deep, dark woods.

Hypocritical and half-baked

Take the Amazon rainforest for example, the setting for unashamed gore-fest Cannibal Holocaust. With the insolence of especially cocky gap year students, four amateur filmmakers make a salacious documentary about local tribes, who respond in kind by dismembering and devouring the invasive upstarts in an act of ritualistic slaughter.

An anthropologist retrieves the footage, setting up a movie-within-a-movie storyline that’s part-horror, part-nature documentary and part-media satire. Unfortunately, with its comic book gore, exploitative casting of real tribes as flesh-feeding maniacs, and juvenile visions of naked ladies writhing in mud while being clubbed to death, Cannibal Holocaust comes across as hypocritical, half-baked and more than a bit rubbish.

On the same continent, at much higher altitude and with infinitely more class, Alive tells the true story of an Argentinian rugby team whose plane crashes in the Andes. At first the survivors feed off each other for emotional support, then literally feed off each other in a bid to stay alive, nibbling on dead passengers to avoid starvation.

The movie makes a clear connection between humans devouring one another for strength, and an oppressive elite harvesting the resources of others

Despite its two-dimensional characters and surprisingly lacklustre emotional punch, Alive shows how cannibalism isn’t the domain of isolated tribes, but something respectable God-fearing folk are more than capable of in the right conditions. And their decision is vindicated too, with human flesh fuelling Ethan Hawke and Josh Hamilton to achieve a superhuman feat of survival.

Conquest and consumption

Superhuman aptly describes Robert Carlyle’s character in Ravenous. A black comedy horror set in California’s Sierra Nevada mountain range in the 1840s, Ravenous channels the myth of the Wendigo, the Algonquin belief that munching on human flesh imbues you with your victim’s power, leaving you invincible, psychotic and addicted to more.

Blending zombie, vampire and serial killer tropes into a weird Deliverance-style dish, Ravenous is good fun and, in its own way, politically acute. Carlyle and co are frontiersmen obsessed with conquest and consumption, and the movie makes a clear connection between humans devouring one another for strength, and an oppressive elite harvesting the resources of others in the name of prosperity.

Ravenous is about the appetite that builds empires, a greed which makes you stronger at the expense of the exploited, but renders you morally weaker in the long-run. There’s no better modern-day example of this than Dr Hannibal Lecter: the educated, sophisticated, cannibalistic serial killer who chews up the psychologically vulnerable in modern-day Baltimore.

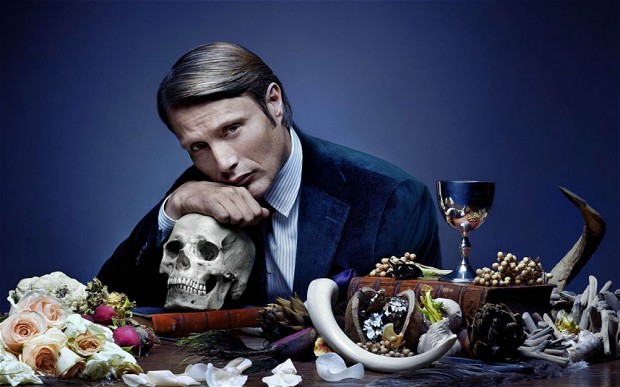

Thomas Harris’s character has brought anthropophagy into the mainstream with wit, panache and amorality, serving up a range of exquisitely sadistic moments, from the closing ‘having a friend for dinner’ line in The Silence of the Lambs to Ray Liotta eating his own brains in Hannibal and Mads Mikkelsen’s sumptuously-depraved lifestyle in the TV show of the same name.

The latter is a vision of a world that’s sick, icy and humourless, where inhabitants seem frozen in perpetual disgust and the most virtuous teeter on the brink of insanity. Epitomising the mood is Dr Lecter himself, pure psychopathy to Will Graham’s pure empathy. An affluent narcissist obsessed with personal gratification, he’s the ultimate metropolitan predator, a member of the professional elite hiding his crimes behind a cloak of respectability and refinement.

Moral cholesterol

Such a bleak power dynamic is flipped gloriously on its head in the charming urban fable Delicatessen. Set in a post-apocalyptic Paris crippled by hyper-austerity, Jean-Pierre Jeunet and Marc Caro’s urban fable tells the tale of an opportunistic butcher and all-round capitalist pig who lures people into his premises at the bottom of an apartment block before slicing, dicing and selling them to hard-up tenants.

The residence has an ecosystem all of its own, an interdependent biosphere where tenants’ lives are interconnected and subject to dietary karma

The feast is spoiled when the butcher’s trembling leaf of a daughter falls in love with an ex-clown, who together team up with a band of subterranean vegetarians to uproot the status quo. Delicatessen creates a deliciously weird tableau of oddball characters, the best one being the apartment block itself. Forever marinated in a sickly green hue, the dilapidated residence has an ecosystem all of its own, an interdependent biosphere where tenants’ lives are interconnected and subject to dietary karma.

A climactic flood washes away all moral cholesterol in the end, cleansing the place of its I’m-all-right-Jacques mentality and restoring a note of much-needed note of harmony. There is such a thing as society, says Delicatessen. And one in which we cannibalise it by living selfishly off each other, whether that be literally or figuratively, is something no sane person should be willing to stomach.

The Links

An Analysis of Michel de Montaigne’s Of Cannibals, The Rugged Pyrrhus, YouTube

Die or Break the Ultimate Taboo, Daily Mail, February 2016

My Crush on Hannibal Lecter, Mashable, October 2018